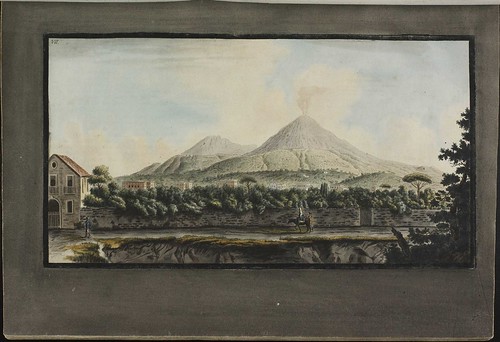

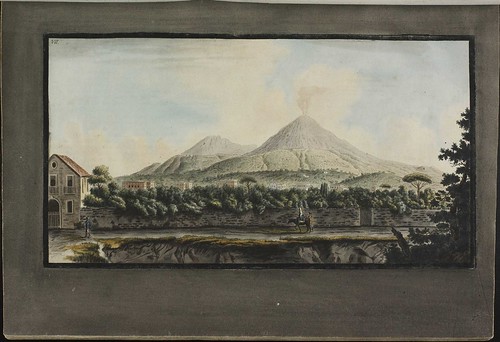

Note: Area around Naples was known locally as the Campi Phlegraei, or ‘flaming fields’, due to the frequent and violent eruptions of mount Vesuvius

View of Naples from Pausilipo

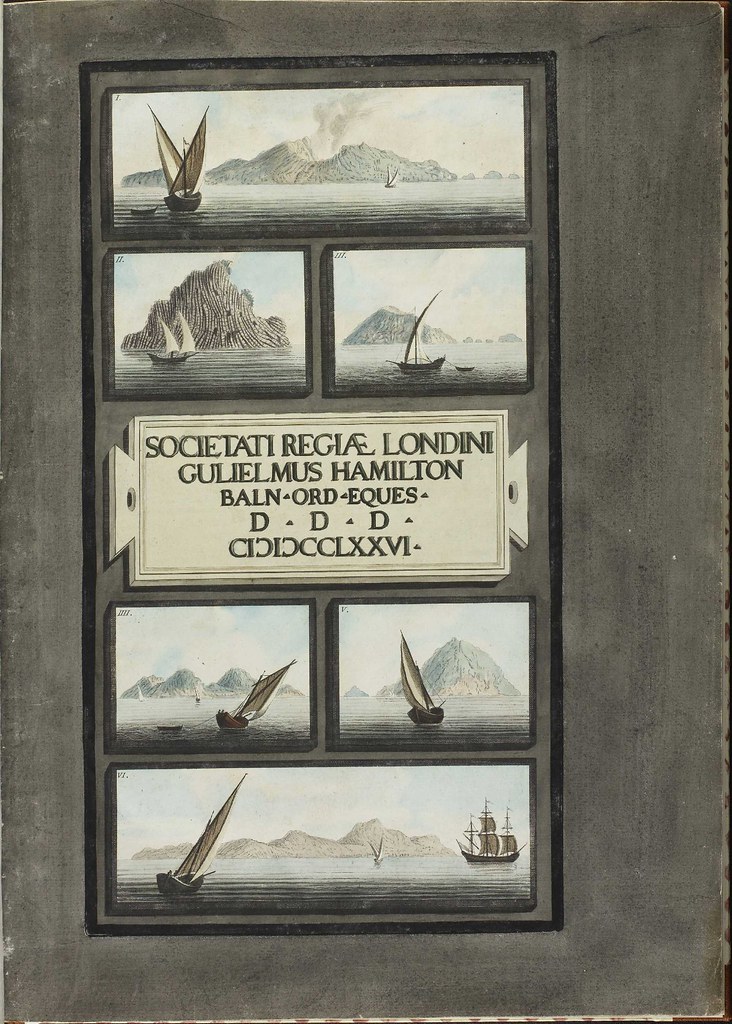

William Hamilton (1730-1803), perhaps best known today as the husband of Emma Hamilton, mistress of Admiral Lord Nelson, was a skilled diplomatist, and natural historian. In his own time he was honoured in particular for his contributions to the study of volcanoes, acquiring the title ‘the modern Pliny’ for his studies of Vesuvius.

Hamilton arrived in Naples as British envoy to the Neapolitan royal court in 1764, and became fascinated by Vesuvius. Shortly after his arrival the volcano went into an eruptive phase that lasted until 1767, giving Hamilton opportunity to observe and report upon its behaviour.

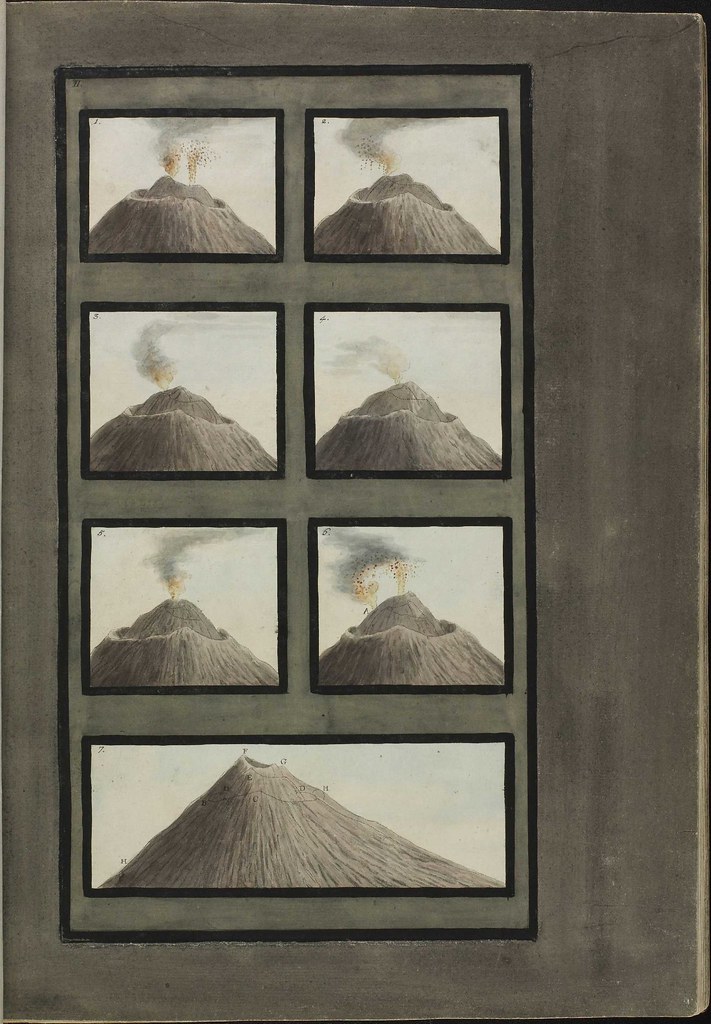

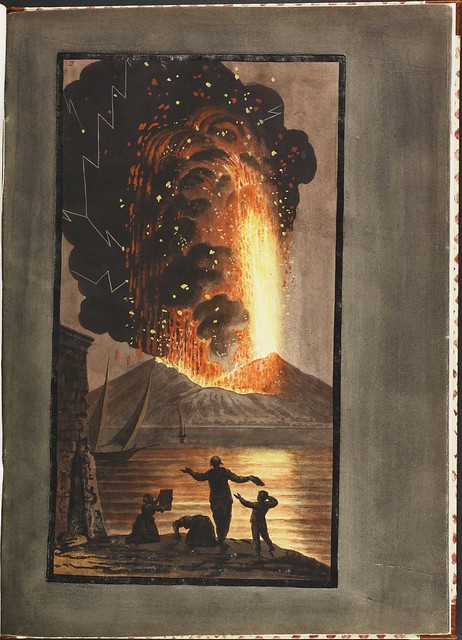

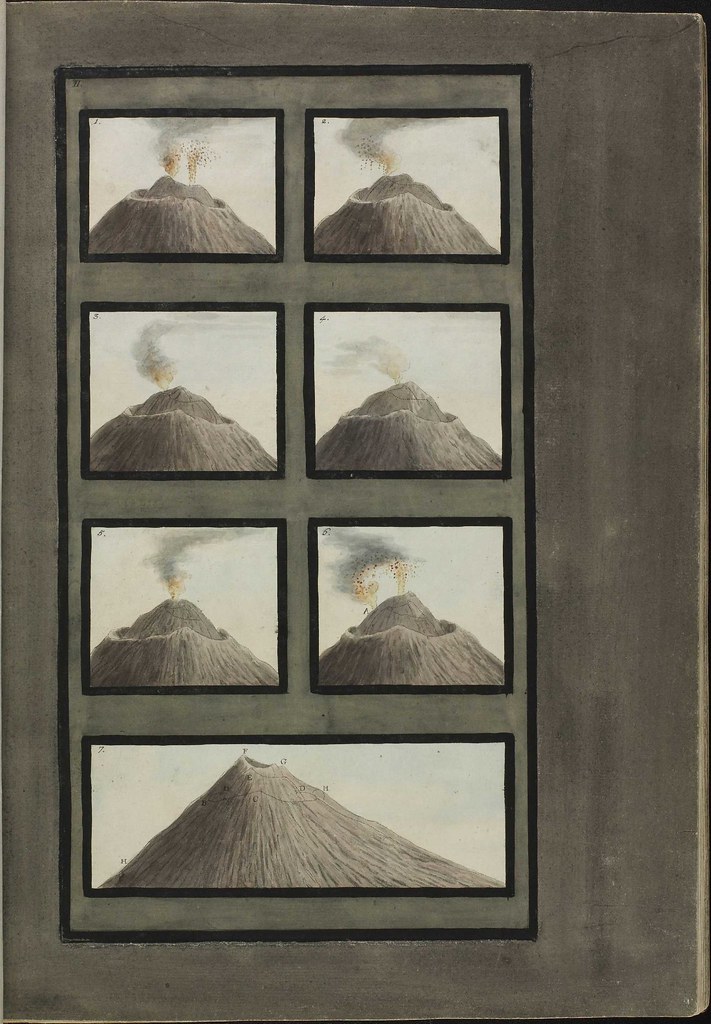

Hamilton believed passionately in the importance of careful, direct observation of natural phenomena, and Campi Phlegraei is intended to make the various aspects of Vesuvius’s activity available to those unable to see the volcano directly themselves.

He ensured that Fabri’s illustrations were as accurate and detailed as possible, reflecting his aim of offering ’accurate and faithfull obſervations on the operations of nature, related with ſimplicity and truth’. The desire to view phenomena directly for oneself, and to form one’s own opinion on the basis of the evidence, can be seen as a central principle of the Enlightenment."

Hamilton arrived in Naples as British envoy to the Neapolitan royal court in 1764, and became fascinated by Vesuvius. Shortly after his arrival the volcano went into an eruptive phase that lasted until 1767, giving Hamilton opportunity to observe and report upon its behaviour.

Hamilton believed passionately in the importance of careful, direct observation of natural phenomena, and Campi Phlegraei is intended to make the various aspects of Vesuvius’s activity available to those unable to see the volcano directly themselves.

He ensured that Fabri’s illustrations were as accurate and detailed as possible, reflecting his aim of offering ’accurate and faithfull obſervations on the operations of nature, related with ſimplicity and truth’. The desire to view phenomena directly for oneself, and to form one’s own opinion on the basis of the evidence, can be seen as a central principle of the Enlightenment."

View of Naples from sea shore

Mt. Vesuvius

Lava eruption on Mt. Vesuvius

Eruption on Mt. Vesuvius 1767 October 20

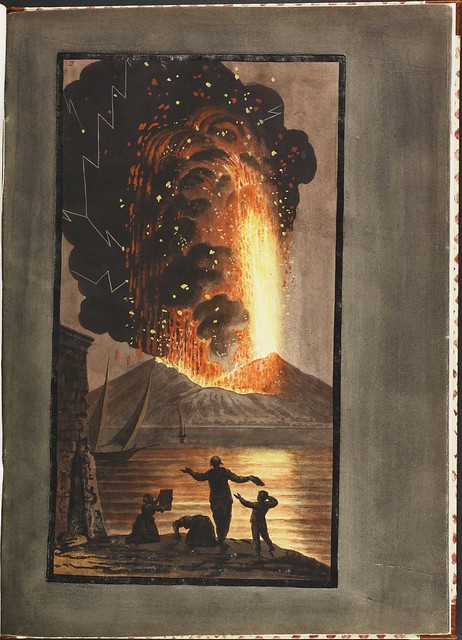

Night view of eruption of Mt. Vesuvius

"A aa lava flow

(recognised by the broken surface texture) passes the observer's

location on 11. May 1771 and reaches the sea at Resina. Note the steep,

slowly advancing front of the flow. Pietro Fabris is amongst the

spectators (below left) as is William Hamilton, who explains the view to

other onlookers." [source]

Eruption of Mt. Vesuvius, 1779 August 9

Top of Mt. Vesuvius

Eruption of Mt. Vesuvius, 1779 August 8

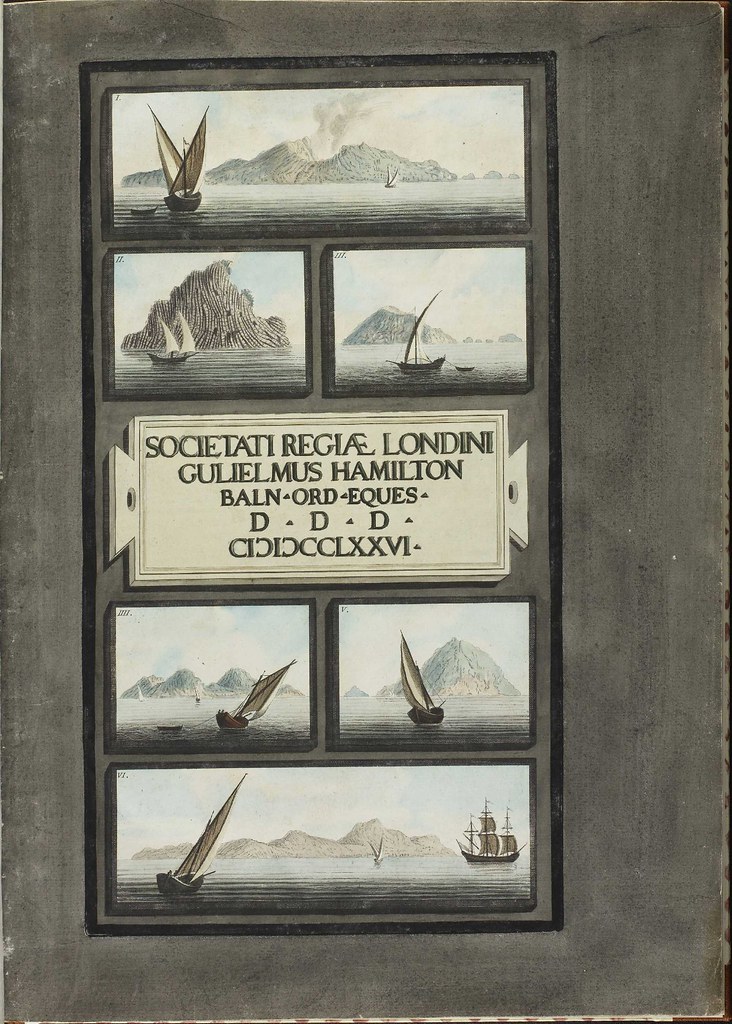

Sailing ships in the Lipari Islands

Crater of Mt. Vesuvius

Crater of Mt. Vesuvius

Mt. Vesuvius eruption 1760 December 23

Stratum of Lava

Island of Ischia

Island of Ventotene

Eruption on island of Stromboli

'Campi Phlegraei'

was published in 1776 with a supplementary volume released three

years later covering the 1779 Vesuvius eruption. The first volume

consists mainly of letters sent by Hamilton to the Royal Society with

the majority of plates appearing in volume two.

The sketches by Pietro

Fabris were reproduced as sixty two engravings for the publication, hand-coloured in gouache.

- The three volumes of 'Campi Phlegraei' are -online- available from Claremont College Digital Libraries. Or best link here for general overview and then click on "browse collections" menu on top

- Sir William Hamilton - Campi Phlegraei: Glasgow University Library Special Collections Department Book of October, 2007

- Volcanological phenomena in the paintings by Fabris and Hamilton.

- Campania Libraries - Land of Myth and History site from Georgetown University: Gallery One has other contemporary engraved plates of Mt Vesuvius.

- 'Sir William Hamilton's Vesuvian Apparatus', 2004 by Bent Sorenson.

- History of Volcanology entries at The Volcanism Blog. {also: Volcanology art}

- The Smithsonian's Global Volcanism Program.

- Wikipedia: Mt Vesuvius; Mt Etna; volcanology; Sir William Hamilton; Emma, Lady Hamilton.